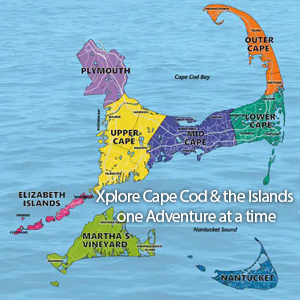

Cape Cod has a long history of seafaring, and thanks to the rips and shoals surrounding the region, subsequently has been home to many historic  Cape Cod maritime rescues and shipwrecks.

Cape Cod maritime rescues and shipwrecks.

The National Park Service reports that there have been more than 3,000 shipwrecks near the Cape in the last 300 years, noting, “It is the shallow sand bars several hundred yards off the beach that present the greatest danger. Here is where storm driven ships ground, break into pieces under the pressure of tons of raging water, and spill their fragile contents and occupants into the bone chilling  surf.” So, it’s no wonder that so many historic Cape Cod maritime rescues have been immortalized in story, book, and film.

surf.” So, it’s no wonder that so many historic Cape Cod maritime rescues have been immortalized in story, book, and film.

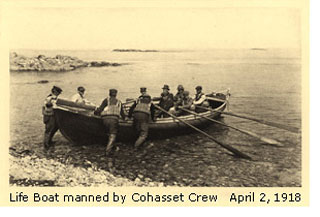

After years of informal rescues, in 1785 the Massachusetts Humane Society established the first organized lifesaving service in the world. In  1872 the group was replaced by a federal group, the U.S. Lifesaving Service, which built several stations along remote dune sections of the Cape. The men of the Lifesaving Service patrolled the beaches and responded to wrecks in surf boats when needed.

1872 the group was replaced by a federal group, the U.S. Lifesaving Service, which built several stations along remote dune sections of the Cape. The men of the Lifesaving Service patrolled the beaches and responded to wrecks in surf boats when needed.

Advances in navigation and communication technology as well as the advent of steel-hulled ships replacing wooden sailing ships, reduced the number of shipwrecks. The Cape Cod Canal, which opened in 1914, also allowed ships traveling between Boston and New York to avoid the stretch on the Outer Cape that had come to be known as the Graveyard of the Atlantic.

In 1915, the U.S. Life-Saving Service became a part of the U.S. Coast Guard. The Coast Guard has been responsible for many historic Cape Cod maritime rescues since its inception.

Located in Buzzards Bay, Joint Base Cape Cod is home to Air Station Cape Cod, the only Coast Guard Aviation facility in the northeast, covering  water from New Jersey to the Canadian border. The base operates using MH-60T Jayhawk helicopters and HC-144A Ocean Sentry fixed wing aircrafts. The Cape and Islands are home to a number of other Coast Guard stations, including Coast Guard Station Chatham, Coast Guard Station Provincetown, Coast Guard Station Brant Point, Coast Guard Station Woods Hole, and Coast Guard Station Cape Cod Canal.

water from New Jersey to the Canadian border. The base operates using MH-60T Jayhawk helicopters and HC-144A Ocean Sentry fixed wing aircrafts. The Cape and Islands are home to a number of other Coast Guard stations, including Coast Guard Station Chatham, Coast Guard Station Provincetown, Coast Guard Station Brant Point, Coast Guard Station Woods Hole, and Coast Guard Station Cape Cod Canal.

Coast Guard Station Chatham is particularly known for one of the most daring of the historic Cape Cod maritime rescues. The rescue took place during a nor’easter in 1952 and has been recounted in the book and subsequent film, The Finest Hours.

Historic Cape Cod Maritime Rescues: The Fort Mercer and Pendleton

The historic Cape Cod maritime rescues recounted in The Finest Hours began with two T2 tankers, the Fort Mercer, and the Pendleton. The ships  were built in 1944 for World War II. The vessels were constructed for quantity over quality, and it was found that the steel used for the hulls had too high of a sulfur content. This flaw meant that the ship’s hulls became brittle at lower temperatures and were prone to splitting in half.

were built in 1944 for World War II. The vessels were constructed for quantity over quality, and it was found that the steel used for the hulls had too high of a sulfur content. This flaw meant that the ship’s hulls became brittle at lower temperatures and were prone to splitting in half.

That’s exactly what happened 70 years ago on February 18th, 1952. The 504-foot turbo-electric T2 tankers SS Fort Mercer and the SS Pendleton split apart in a gale battering the Cape. The storm produced 70 knot winds and 60-foot waves, freezing temperatures, and brought massive snowfall to much of New England. The Fort Mercer was able to send out a distress call, and the Coast Guard mounted a response, sending cutters, lifesaving boats, and an airplane to assist in the rescue of the vessel, located 20 miles off the coast.

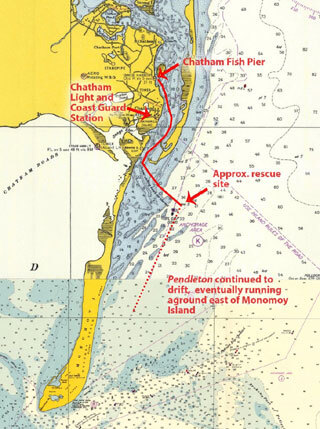

The Pendleton, 10 miles off the coast of Chatham, however, wasn’t able to signal for help before the vessel lost power and split in two. The crew from Coast Guard Station Chatham was already out on the waves attempting to rescue the crew of the Fort Mercer when radar at the Coast Guard Station showed an object that turned out to be a section of the Pendleton drifting towards Monomoy.

With Coast Guard Station Chatham already occupied with the rescue of the  Fort Mercer, four young Coast Guardsmen volunteered to attempt a rescue of the Pendleton. Led by Coxswain Bernie Webber, Coast Guardsmen Ervin Maske, Andrew Fitzgerald, and Richard P. Livesey set out in a 36- foot boat. The wooden motorboat, known as CG-36500, was not a large vessel and was meant to hold no more than 12 mariners.

Fort Mercer, four young Coast Guardsmen volunteered to attempt a rescue of the Pendleton. Led by Coxswain Bernie Webber, Coast Guardsmen Ervin Maske, Andrew Fitzgerald, and Richard P. Livesey set out in a 36- foot boat. The wooden motorboat, known as CG-36500, was not a large vessel and was meant to hold no more than 12 mariners.

The unofficial motto of the Coast Guard, attributed to Patrick H. Etheridge, Keeper of the Cape Hatteras Life-Saving Station, is along the lines of, “You have to go out, but you don’t have to come back.” The Coast Guardsmen were no doubt thinking that as they headed towards the Chatham Bar in hopes of rescuing the Pendleton.

If you visit the Chatham Fish Pier or Chatham Lighthouse and look out toward the Atlantic, you’ll notice the sandbars protecting the harbor that make up the Chatham Bar, a treacherous navigational hazard. The ever-shifting shoals at the mouth of Chatham Harbor are a challenge to navigate, even in calm seas. And the weather on that February day in 1952 was anything but calm.

When crossing the breakers and surf of the bar, the CG-36500 was slammed by a large wave, knocking the vessel on its side, shattering the windshield, and sweeping the only navigational aid, a compass, into the froth. Still, the Coast Guardsmen pressed on, navigating by feel and eventually finding the stern section of the Pendleton. Even once the foundering boats were found, staging the rescues was a challenge.

After several attempts, the men on the CG-36500 were able to bring 32 of the 33 men on the stern section onto their 36-foot lifeboat. Tragically the last man leaving the stern section, George “Tiny” Myers was lost to the sea after helping his shipmates make it to the rescue vessel.

The overloaded vessel, now with 36 men aboard including the rescuers, headed back towards Chatham. They managed to cross the treacherous bar for a second time and headed for the Chatham Fish Pier. The stern section continued drifting, eventually grounding off of Monomoy, and settling under the waves.

On the Chatham Fish Pier, a crowd had gathered in the storm, waiting for the return of the vessels. Across the Cape, people had been listening to radios, hearing reports of the daring rescue and imperiled vessels as the storm raged outside.

On the Chatham Fish Pier, a crowd had gathered in the storm, waiting for the return of the vessels. Across the Cape, people had been listening to radios, hearing reports of the daring rescue and imperiled vessels as the storm raged outside.

The remarkable rescue came to be known as the greatest and most daring small boat rescue in the Coast Guard’s history. The historic Cape Cod maritime rescues of that storm warranted Gold Lifesaving Metals, the Coast Guard’s highest honor for many of the rescuers.

The CG-36500 continued serving as a Coast Guard vessel until it was retired in 1968. It was neglected until the Orleans Historical Society acquired and restored the boat beginning in 1981. The vessel can be visited at Rock Harbor in Orleans during the summer months.

The tale of bravery and courage is told in more detail by Casey Sherman and Michael J. Tougias in The Finest Hours: The True Story of the U.S. Coast Guard’s Most Daring Sea Rescue and the subsequent film by Disney.